LONDON — President Donald Trump hasn’t started a war. But he’s spent his first year in the White House at war, and his military has dropped a record number of bombs on the Middle East.

Unlike many of his predecessors, Trump’s vision for U.S. foreign policy is crystal clear and summed up in two words: “America First.”

Acting on this, he abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal and pulled out of a global climate agreement. But this has led to “America Isolated.”

Trump has positioned himself, at home and abroad, as the “disruptor in chief,” a political insurgent throwing stones at the establishment on behalf of the people who elected him. He relishes it.

But as a result, the U.S. is standing alone on more key global issues than ever before. And America’s seductive sheen of “soft power” — the ability to get what they want through attraction and persuasion — has been diminished.

Trump has praised the presidents of global rivals Russia and China, while criticizing the leaders of America’s closest allies Britain and Germany. He has also sowed doubt about America’s commitment to its oldest alliances, such as NATO.

It’s too early to say whether Trump’s foreign policy has been a success or failure. However, several things are clear.

Middle East and Afghanistan

In one war, Trump can claim success. His airstrikes have helped to end the Islamic State group’s rule in Iraq and Syria.

It’s too early to call it complete victory, but Trump’s — and Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin’s — bombs spoke louder than Barack Obama’s words.

The terror group’s “caliphate,” proclaimed in Iraq’s second-largest city Mosul and headquartered in the Syrian city of Raqqa, has collapsed.

However, the remaining ISIS fighters have scattered.

The “blowback” against the U.S. and Europe may yet come, as those fighters refocus their campaigns and some return to the West.

But the defeat of ISIS is clear. It came at a cost. Trump dropped a record number of bombs on the Middle East — around 40,000 on Iraq and Syria.

As a result, civilian casualties under Trump reached an all-time high in Iraq and Syria, according to Airwars, which tracks international airstrikes against ISIS using official figures.

Anger at American airstrikes and at the presence of thousands of U.S. troops — including 2,000 in Syria alone — may yet set back counterinsurgency efforts in the region.

Elsewhere in the Middle East, the Trump record is murkier.

Perhaps no president — not even George W. Bush invading Iraq in 2003 — has lined up more nations against a single policy as Trump did when he recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

From European allies to global rivals like China and Russia, from Iran to the Vatican, his move was denounced. It is hard to see what Trump gained the U.S. by doing it, easy to see how he delighted his base at home.

The “Middle East peace process” has made no obvious progress; it’s a phrase beloved of policymakers and journalists that cloaks a desert of failure and frustration.

Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner has been put in charge of it, with little to show so far. This, after Trump boasted that peace between Israelis and Palestinians “is something that I think is frankly, maybe not as difficult as people have thought over the years.” Officials suggest there may be something to announce in early 2018.

Trump has also been at war in Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen as he targets ISIS, al Qaeda and their affiliates.

He signaled a change in policy in Afghanistan, announcing 4,000 extra American troops to help the 11,000 already there. He also dropped nearly 4,000 bombs on the country, including the largest non-nuclear bomb ever detonated.

Iran

Trump sent a signal to the region with his first trip outside America.

He chose not to hop over the border to Canada or Mexico, as every other recent president has done, but to instead visited Saudi Arabia.

It sent a message of solidarity to the Sunni Muslim world — but perhaps an even stronger one to Shiite Iran.

If Tehran sees one enemy greater than Washington, it’s Riyadh.

And Trump has Iran in his sights. In his campaign Trump promised to support Israel, confront Iran and get out of other people’s wars in the Middle East.

Despite his campaign promise to scrap the Iran nuclear deal — “the worst deal ever negotiated”— on Day One in office, he hasn’t yet done so.

But in October he decertified the nuclear deal, turning his back on a U.S. commitment without providing evidence that Iran was reneging on the deal. The International Atomic Energy Agency says Iran is complying with the terms of the deal.

He claimed Iran provided assistance to al Qaeda, a highly contentious assertion.

He has hawks in his administration who believe the road to solving the problems of the Middle East runs through Tehran. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis once described the three biggest threats to America’s national security as “Iran, Iran, Iran.”

Trump has identified Iran as a centre of instability in the Middle East; the crosshairs are settling on the nuclear deal, which he would love to kill and may yet.

But so far, Trump has refrained from openly confronting what is a relatively moderate regime in Tehran, at least by its revolutionary standards.

China

The tectonic plates of global power are shifting. Four powers — the U.S., China, the E.U. and Russia — are jostling for global influence.

In his December national security speech, Trump stated the obvious and presented China and Russia as competitors wanting to realign global power in their interest, potentially threatening the United States.

“Whether we like it or not,” he said, “we are engaged in new era of competition.”

Critics have been harsh.

Trump has “made the world safe for Chinese influence,” says Richard Haass of the Council on Foreign Relations.

In the newspaper Trump describes as “failing,” the New York Times, Thomas Friedman says “in nearly 30 years of covering United States foreign policy, I’ve never seen a president give up so much to so many for so little, starting with China and Israel.” He calls it “the art of the giveaway.”

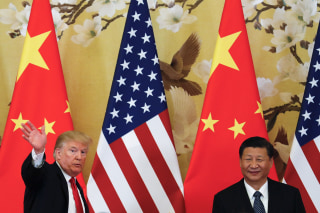

On the second of two long presidential trips, he visited Beijing and, as with the Middle East tour, managed not to step on diplomatic landmines.

The Asia tour was notable for a bland encounter with China’s President Xi Jinping, in which Trump held back from criticizing him, but made what may become one of the defining statements of his presidency; asking “who can blame a country for being able to take advantage of another country for the benefit of its citizens?” On that logic potentially rests the invasion of other countries.

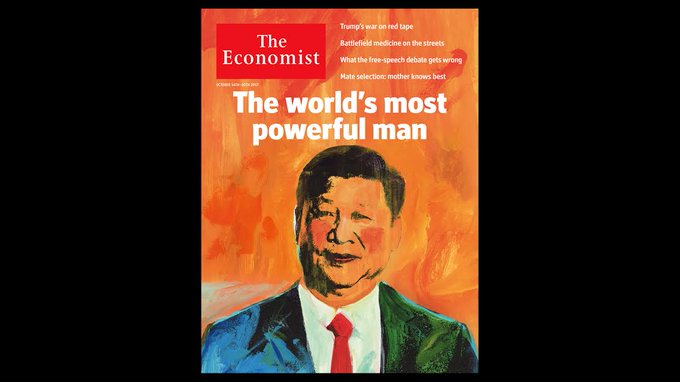

Before the visit had even begun, the Economist magazine named Xi, not Trump, “The World’s Most Powerful Man.”

And it is Xi, not Trump, who has positioned himself as the defender of globalization and the climate.

In the “dance of great powers,” it’s Xi who’s doing the tango and Trump who’s tapping his foot to the music, shunned by prospective partners.

Xi not only understands English but he has learned to use the rhetoric of global leadership and China is filling the void that Trump has left behind.

On his first day in office he ripped up the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade deal, the biggest in history, binding 12 allies including Australia, Japan and Canada.

The bloc controlled 40 percent of global trade and the U.S. might have headed it for years, pressuring China to open its markets.

North Korea

Even Trump’s harshest critics would accept that the U.S. has no good choices on North Korea, which has been called “the land of bad options.”

Trump has declared “the era of strategic patience” over and few argue with his contention that 20 years of such an approach has failed to stop Pyongyang building a nuclear arsenal that can target, and possibly reach, the U.S. mainland.

Perhaps the most startling phrase uttered by any leader this year was Trump’s off-the-cuff “fire and fury” threat to North Korea.

Related: How Kim bested Trump in the slugfest that was 2017

His repeated taunting dictator Kim Jong Un — calling him “rocket man” and a “sick puppy” — set pulses racing among allies and adversaries alike and raised fears of miscommunication with devastating consequences. In September, Kim’s foreign minister said Trump had “declared war” on North Korea. The White House rejected that suggestion as “absurd.”

North Korea has now been designated a “state sponsor of terror” and Trump has threatened its “total destruction.”

War may not come but the American goal of the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula is no closer to being achieved.

Climate change

Under Trump the United States stands isolated on the issue of climate change and how to tackle it.

Trump’s decision to pull out of the 2015 Paris climate accord was denounced around the world.

Since then, the U.S. has become the only country in the world not to sign.

Syria joined up in November, following Nicaragua a month earlier.

Trump also removed climate change as a threat to America’s national security from his 2017 national security strategy.

At climate talks in Germany in November, the White House pushed coal and nuclear power while representatives from U.S. corporations and cities marketed renewable energy.

Russia

In Russia, all hopes that Trump would improve relations with Moscow and usher in a new period of cooperation with President Putin, are dead.

Influential Russians believe the American “deep state” has made it impossible for Trump to reset relations.

Putin and Trump’s long predicted “bromance” hasn’t materialized.

In his national security review, Trump identified Russia as a key competitor and there is no sign that he is ready — or politically able — to lift economic sanctions on Moscow.

But Trump’s America and Moscow are not enemies as they were in the days of the Cold War.

America’s allies

Trump has needlessly alienated the U.K., America’s closest ally by retweeting inflammatory anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant videos from a far-right group and then criticizing Prime Minister Theresa May. He also blasted London Mayor Sadiq Khan as the city was reeling from terrorist attacks.

His visit to Europe was not judged a success with the Financial Times calling it “crass” and “disastrous.”

Trump unsettled NATO colleagues by declaring the alliance “obsolete” in January, only to roll back that judgment to “no longer obsolete” in April.

But it was enough for German Chancellor Angela Merkel to state bluntly “the times when we could rely fully on others are somewhat over; we Europeans must really take our fate into our own hands.”

Earlier this month, Trump threatened to cut “billions” of dollars in aid to countries that defy the U.S. at the United Nations.

Since the Second World War, the United States has been the security cornerstone of the West, but Trump broke with 70 years of tradition. He refused to reaffirm the alliance’s bedrock commitment to mutual defense, hectored other NATO leaders at length and elbowed aside Montenegro’s prime minister.

His personal behavior has grated with many leaders. More worrying was the new president’s seeming contempt for core Western values. The world’s most powerful state was seen to be sabotaging the order it created.

The future

Trump inherited an international order in flux, and one that was crumbling in some areas.

Russia and Islamist militants were redrawing the map at gunpoint; Obama’s record in the Middle East was patchy, declaring a red line in Syria on the use of chemical weapons and then walking back from it, seriously damaging America’s global reputation.

It’s still not clear where Trump’s foreign policy will take the U.S. And it’s certainly too early to pass judgment on whether he can “make America great again,” at home or abroad.

But it appears likely his combativeness will continue as he challenges accepted norms, shatters diplomatic traditions and responds to slights with thin-skinned aggression.

It’s too early to call anything “Trump-ism”— except perhaps disruption itself. He is not yet defined by Nixon’s “Madman theory” — that he can frighten any adversary into bending to his demands. One lesson global leaders are learning is that if challenged, Trump often doubles down.

But Trump is also learning. He criticized China for failing to restrain North Korea’s missile tests but then changed his mind after talking with China’s President Xi.

“After listening for 10 minutes, I realized it’s not so easy,” he told the Wall Street Journal.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson recently said the U.S. has made progress on issues like North Korea, but earlier this month conceded that the administration did not have any big victories yet. “Do we have any wins on the board? No. That’s not the way this works. Diplomacy is not that simple.”

Nor, as Trump is discovering, is governing.

*News Searching By nbc*